Everyday Systems: Podcast : Episode 66

Right Relationship with Robots

Hi, this is Reinhard from Everyday Systems.

I’m going to tell you a little story about my Roomba robot vacuum cleaner that may not seem immediately relevant to Everyday Systems, but bear with me – I am, in a meandering way, going somewhere with this.

I got my Roomba toward the beginning of the pandemic. I figured it might help with the exponentially greater mess of us all being in lockdown without options for extra human assistance. But I was curious more than anything. And whatever the Rooma’s merits as a vacuum cleaner, my curiosity has been abundantly satisfied.

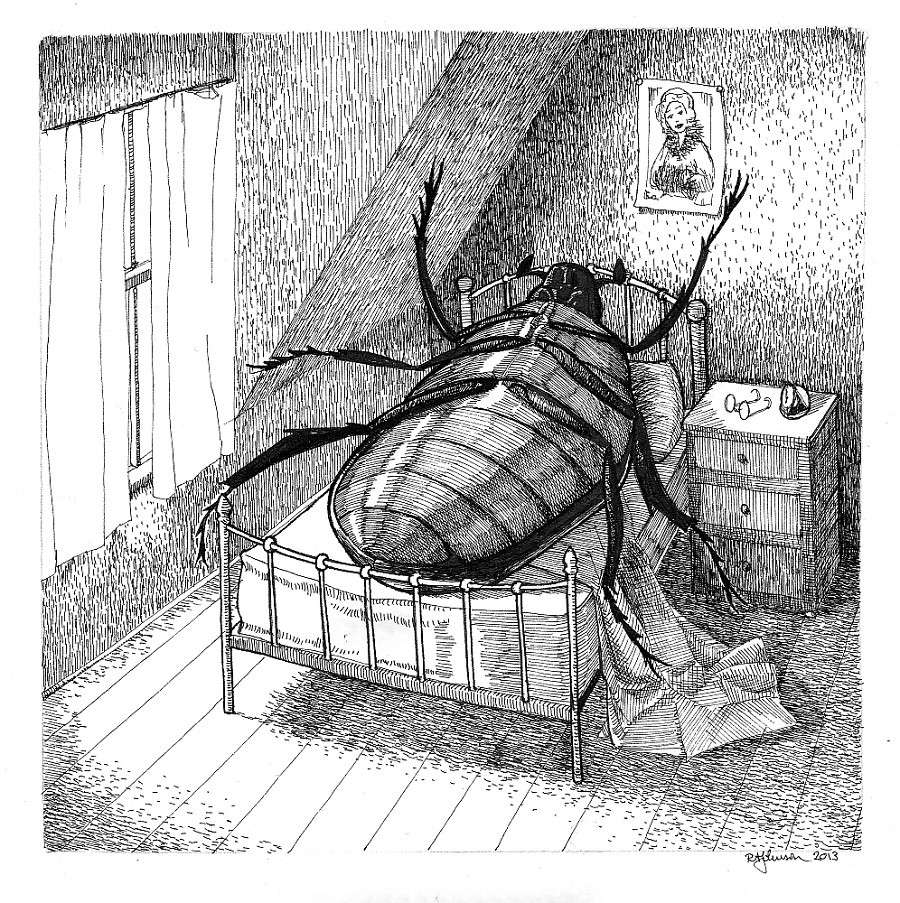

As you may know, when you first welcome a new Roomba into your home, the first step is to name it. The app insists on this. I wanted to call it Gregor Samsa, after the character in the Franz Kafka story, The Metamorphosis, who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a gigantic insect. The roomba looks a bit like a robotic pillbug, and ours lives under an old piece of furniture when not in use, hiding, I thought, like Gregor Samsa, from human eyes.

But the kids refused to get this reference, and insisted we call it Poomba instead, some Disney reference I refuse to get. In an attempt to endear them to our new robot friend, I let them win on the name, but that concession was for naught, they hate the darn thing. They hate the noise it makes, They hate that we have to leave doors open for it to get through. They hate that it gets in their business when they’re trying to focus on Genshen or Minecraft or whatever other worthy activity they might be engaged in. My young son’s aversion was so intense that I was a little concerned he might physically attack it, but he was a little too scared of it to go that far.

I initially thought the kids might develop some sort of animistic attachment to the thing – I think I might have. If kids can imagine that teddy bears have personalities, why not a robot that moves and talks? But I guess there’s a reason teddy bugs are not a thing: its hard, invertebrate carapace just doesn’t inspire that sort of feeling.

In terms of its performance, it’s definitely not been as magical as I’d hoped it might be. I had visions of basically not thinking about the chore of vacuuming at all while Gregor Samsa aka Poomba autonomously did his thing. But that did not come to pass. At first, I could rarely get it to complete a single run without having to rescue it. I’d be out for a walk or in the big empty public library where I was one of the few staff still working onsite and my phone would light up with an SOS from Roomba. It would get stuck under the dishwasher, its rotors would get gummed up with facemasks, hair elastics, pencils, socks, mardi gras necklaces, charging cords, notebook paper, and most of all, long luxuriant strands of human hair, courtesy of my wife and daughters.

The hair in particular was a challenge. It wouldn’t just gum up the rotors, great coils would accumulate around the rubber rollers and actually cut through them, cut them right in half after enough runs. And the replacement rollers were expensive. Hair would twine under the main spinner to such an extent that it would first slow down and then stop spinning entirely, and I couldn’t address or even fully see the problem without unscrewing and removing the spinner with a screwdriver.

The only good thing, I guess, was that it actually did slurp up dirt every time I ran it – disturbing quantities of dirt. So it was effective in that sense, more so than I’d thought it would be. But that also meant I had to empty it every single time it ran because its little belly would always fill up, and I’d get another plea for help on my phone: “empty the bin.” They sell docking stations that supposedly let it auto empty itself, but I couldn’t see the point since I had to de-gum its rotors after every run anyway and manually emptying the bin didn’t add much more time to that.

My initial reaction to all this was: I need a more powerful robot. Maybe an upgraded military-grade version of the Roomba, one with sharp steel blades and a flamethrower, to cut through the mess of our filthy house. And then, more despondently, since I was fairly certain such a thing didn’t exist (at least for civilian use), I’d think: Roombas are for people whose houses are basically clean already, neat freaks who want to crank the cleanliness up to 11, not slobs like us.

But then I thought, no, I’m not going to give up, I’m going to work with it. I’m going to partner with my robot. I’m not going to wait for the pathetic cries for help on my phone. I’m going to pre-emptively, posifactively, routinely do all the maintenance tasks, before every run, and not get irritated or surprised that the Roomba isn’t magic.

First off, I run it when no one is in the house but me (since I now work from home). Five days a week, Monday through Friday. That takes care of the irritated family members problem.

Secondly, I run through the house tidying before each run, picking up potential booby traps like hair elastics, facemasks, iphone chargers, etc., and getting the place “Roomba ready.” The truth is back when we used a cleaning service every couple of weeks half the benefit was that it embarrassed us into pre-cleaning so the maids wouldn’t see what slobs we were. A robot, it turns out, can provide that benefit too; it can guilt trip you into pre-cleaning. I also move furniture around that might impede or trap the Roomba, and block off the front of the dishwasher with two chairs so it doesn’t get caught in the gap between the dishwasher and the floor, which is exactly the right height to trap it without it’s sensors being able to detect and avoid the danger.

Thirdly, I grab a pair of scissors and a phillips screw driver and clear the rollers and spinner of the coils of human hair that have wrapped around them from the previous run. I don’t fool around anymore, I take the parts completely off to get better access to them. Once I’ve gotten the rollers out, I even take the endcaps off to get at the hair that’s underneath them. I’ve gotten really quick at this whole process. I feel like a formula one race car technician changing tires between laps.

Finally I empty the dustbin, which is almost certainly full enough for the roomba’s delicate little sensors to feel stuffed. I don’t bother wiping the sensors anymore because I know there’s no point, it’s always going to think it’s full, and it’s easier to just habitually empty the dustbin before every run. I’m not bothered by this preemptive emptying because it’s the least time consuming of all the necessary maintenance tasks.

Then I run the darn thing. And thanks to my new prep routine, it usually doesn’t need to be rescued any more. It cleans my whole apartment, minus the girls bedroom, which contains easily terrified bunnies and I’ve ceded as lost territory to the enemy, in about two hours. When all’s said and done, our home is cleaner than it would have been otherwise, and in less time (active time) than it would have taken me to do it with my 25 year old Miele canister vac.

Why am I telling you this story? Not because I am getting kickbacks from Irobot. I doubt I would have ever bought the darn thing if I’d known what I was getting into – though I guess I consider it a qualified (heavily qualified) success now. And the kicker is, even after all my preemptive routine maintenance, it still gets stuck often enough that I”m not sure even all this would be sufficient if I weren’t also working from home and poised for rapid rescue.

So why then? What does it have to do with everyday systems?

Well, among other things, I think my relationship with my Roomba – my struggle to establish it, my ongoing struggles to maintain and develop it – is emblematic of how many of my habit systems relate or encourage me to relate to technology. Because most of them do, even though it might not be immediately obvious.

Generally speaking, the Everyday Systems encourage a balanced relationship with technology. They encourage you to use and embrace it when it makes sense – and to keep a wary distance when it doesn’t. They also acknowledge that technology is changing, and that part of the relationship with technology is reevaluating it continually.

Weekend Luddite is explicitly about technology and explicitly about this balance – I engineer extended breaks from the screen on weekends (with certain whitelisted exceptions) but accept that I have to use technology fairly intensively during the week. As new apps and new devices and new social conventions and pressures around how to use those apps and devices proliferate, I keep having to reassess where and how I draw my lines between permissible and non-permissible uses of technology. Is this app or use of this app, allowed during my luddite time? Does it make a difference if I am using it solo or with other human beings? The balance between clear lines and realistic, sensible ones is hard to find. But so far (you never know what new system-blasting new development is just around the corner) I feel I’ve been managing.

This balancing act with technology is also present in many of the other systems, though maybe just implicitly, so let me surface it a bit.

Shovelglove is saturated with nostalgia for the pre-digital age of manual labor. You don’t need a thousand dollar internet connected machine that might give you a heart attack. You don’t even need an app. And yet I’m usually watching some sort of streaming video while I’m driving fence posts, churning butter etc. So in practice, there is some technology involved. And I’ve come to find it a benefit, both motivationally in terms of getting me to do Shovelglove, and, since I’m usually watching something somehow instructive, as part of my Study Habit.

As an Urban Ranger I also eschew fancy gym machinery – between glances at my fitbit. When I started Urban Ranger I didn’t have a pedometer, and it was just fine. I only got the fitbit to spur my daughter on in friendly competition. But I’ve come to appreciate the unobtrusive tracking. It’s nice to get credit for every little movement, sets the bar almost infinitely low even when I’m feeling most sluggish and overwhelmed. It’s very VC Cat in that regard, giving me a medal of sorts (a step counted) for even the tiniest effort. And apparently, on a macro societal level, step trackers really do encourage a statistically significant (and public health-wise significant) number of extra steps on average [get stat from the economics tech quarterly].

On the No S Diet I am not punching in carbs or calories via some app – but I do track red, yellow or green compliance on my “habit calendar” spreadsheet (aka, my life log, where I also track other habit compliance stats, including weekly data dumps from my fitbit and smart scale). There is now a whole ecosystem of habit tracking apps, many of which have been discussed on the facebook group, and I think this is a good thing (though I humbly suggest a spreadsheet may be the best of them all).

Personal Punch Cards are proudly analog – the non-digital physicality of the index cards is fundamental to why this system works, the limitations of the physical medium keeps my task hubris in check. Only so many todos can fit on my daily 3x5 index card. And yet – the metaphor is from computing. Obsolete retro computing maybe, but computing nonetheless. And every week I lovingly copy portions of the information on those physical index cards into my digital lifelog spreadsheet.

G-ray vision – this is like augmented reality via a Jedi mind trick – a mental AR filter. Or maybe de-augmented “digitality,” since it’s subtractive, and its target is the opposite of reality. It’s about how to be online in a healthier way by mentally filtering out a certain aspect of it. I’m actually surprised by how little I have had to change about this system since I started practicing it; I guess the big changes in this domain (VR and what not) are happening outside my view (which is the point).

The Study Habit, which involves displacing compulsive phone diddling with productive or even elevating phone use – reviewing anki flashcards – is probably a wash in terms of total screen time. I’m not sure I spend any less time on my phone because of it – but the time I do spend is qualitatively enhanced in a very significant way. The guy next to me on the train is stressing about his frenemies on social media; I’m memorizing poetry.

Timebox Lord makes extensive use of a timer – which happens in practice to be a computing device more powerful than the one that sent the Apollo astronauts to the moon. Some people use meditation apps to get away from the app-[induced] frenzy of their everyday lives, fighting fire with fire. I don’t, but I do use the timer on my phone. And even though I might be restricting myself to that one simple app – the timer – there is a danger to be managed by keeping the rocket powering distraction machine so close at hand. Technology assisted mindfulness seems wrong somehow. And I think it can be a trap. Every time you’re about to start the timer or meditation app you have to remember to dodge facebook, etc,. But maybe practicing the right use of technology, practicing that dodging can be a kind of mindfulness in itself.

Even explicitly religious practices, which I want to put in a category diametrically opposed to technology, are not always incompatible with it. I read an article recently describing how many devout Muslim’s use prayer tracker apps and devices – a ring which is sort of like a prayer fitbit – to track how many times a day they recite their prayers. I wish I prayed frequently enough to need an app to track it, but I do note the little I manage on my punch card and lifelog (FRABCRYMS!), and after reading this article, I feel slightly less weirdly wrong about doing that.

Sometimes I think, I wish I could be a straight up luddite, and not just on the weekends. I look at the old order Amish and think “those guys have got it right.” Wouldn’t it be better, if instead of getting intimate with my robot vacuum cleaner, I swept the floors by hand instead? If I used a hand wound timer instead of a pocket supercomputer to regulate my Shovelglove, meditation, and Timebox Lording? Wouldn’t it be cleaner, spiritually?

It might. And yet, I don’t think in my situation in life, scrambling to transmute keystokes into my family’s daily bread, salvaging every spare minute to get the kids fed, out of the house and where they need to be on time, and the disaster they leave in their wake contained, that that’s really an option for me. Maybe I could tweak a little around the edges, keep a little more distance than I currently am. But somehow I’m going to have to work rather intimately with technology as my (problematic) ally, without letting that alliance corrupt me.

So circling back to my Roomba.

You’ve probably all heard some version of that famous quote, sometimes known as Amara’s Law, which has been attributed to so many people that I can’t even get to the end of the quote investigator article about it:

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate its effect in the long run.”

Well, I can’t say that’s exactly how it’s gone with my Roomba. But I definitely had a period of magical expectation, intense let down, and then, increasing (if qualified) appreciation. And of course it ain’t over yet; the thing’s algorithms are continually being tweaked and improved every software update, and there are already new models. Who knows? Maybe it will suddenly become magical. Or problematic in some unanticipated way. I’ll have to keep reassessing. I’ll have to keep tweaking and refining my habits around how I use it, and rely on it, and think about it. And I’ll have to do that with all my systems as technology increasingly pervades everything.

While most of my habit systems involve technology somehow, either actively as a support, or re-actively by keeping it at bay, this thing I have going on with my Roomba is the first system that is specifically, positively about technology and how to use it. It feels funny to call it a habit, but it is. I run it on N days. I give it a rest on S days. I perform a precise litany of tasks. The robot is supposed to do things for me, not the other way around. But it turns out it’s a bit of both. And I suspect, as technology evolves, there will be more systems like this. Beyond being emblematic, Right Relationship with Robots might even be a system, or a family or systems, unto itself.

Well, that’s all I’ve got for today. May you neither a 24/7 by 365 luddite nor a techno utopian be. And may your relationships with all your household appliances stay healthy and productive. Thanks for listening.

© 2002-2022 Everyday Systems LLC, All Rights Reserved.