Everyday Systems: Podcast : Episode 92

The Wisdom of Games

Hi, this is Reinhard from Everyday Systems.

During the pandemic, like a lot of cooped-up people, my family played a lot of board games. We’d always liked board games, to a degree, but the pandemic took it to a whole new level. And I’m grateful. Not just for the direct fun and together-time these games brought us, and how they knocked me out of my workday worries more effectively than anything else, but because I think I really learned some larger life-lessons from them, some practical inspirations for Everyday Systems and even a kind of wisdom. A good game is a distraction from real life but it’s also in some sense a distillation of it.

I had a premonition of this when our older daughter, now in college, was a preemie and had some developmental delays. When she was very small she went to a therapist who basically just played Sorry with her. At the time we thought it was a trifle ridiculous. This guy was not cheap, Dr. Sorry, M.D. But in retrospect, I think it may have been a sound approach. And I guess I should be grateful he reached for the board game instead of the psychopharmaceuticals. She learned how to deal with disappointment – that’s probably Sorry’s biggest life lesson, built right into the name. She learned how to compete with people while still respecting and caring about them, that an opponent is not an enemy. Basic but important stuff, and stuff she was having trouble with.

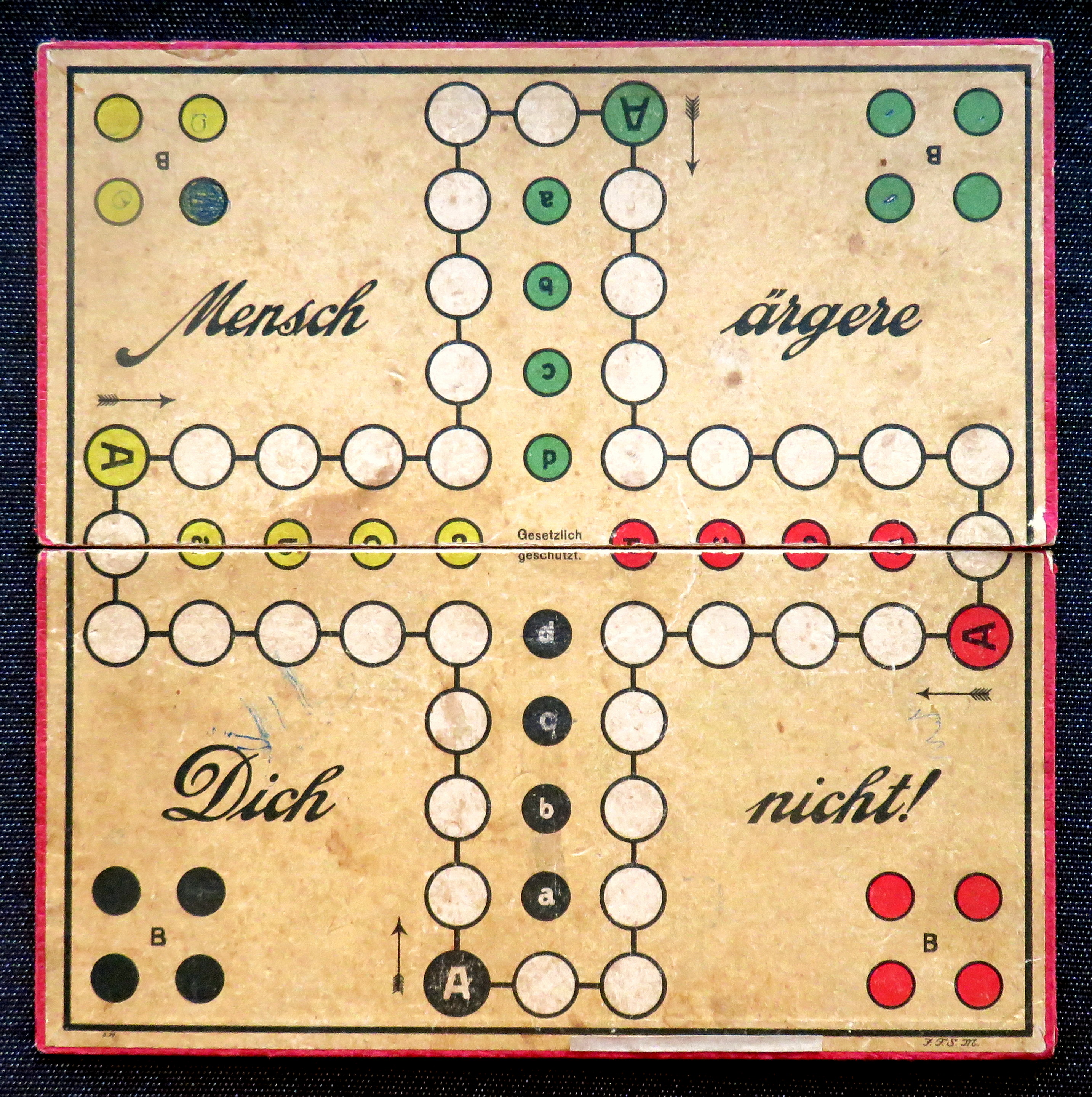

Sorry is apparently based on a German game I played as a child with a name that’s even more psychologically revealing: it’s called Mensch ärgere dich nicht or “Man, don’t get mad.” Now that I think of it, I can totally imagine Freud, Jung and Adler at a cafe in Vienna, sorting out their psychoanalytic schisms over a game of Mensch ärgere dich nicht.

The games we’ve been playing recently are a little more sophisticated than Sorry: Seven Wonders, Citadels, Smallworld, Pandemic, Settlers of Cataan (of course), Agricola, Bohnanza, Century, Viticulture, Splendor, Libertalia, Scythe and above all, Wingspan – mostly fancy European-style board games. I don’t know if the wisdom they contain is any more profound than Sorry for being sophisticated, but it’s also wisdom, other wisdom, maybe not quite so obvious, and also valuable. In this episode I’d like to discuss some specific mechanics and aspects of these games that I’ve found helpful in thinking about Everyday Systems and human life in general. I guess it also doubles as a games recommendation episode; the games I’ll be discussing are great as games even if you’re not in the market for whatever wisdom they might have to offer.

Several of Everyday Systems podcast episodes have been inspired by that Gesamtkunstwerk of games, Dungeons & Dragons, which combines randomness and skill with a kind of improv theater. There was Lawful Good Biker, Demogorgon vs. Asmodeus, Demogorgon Whack-a-mole (which was two games rolled into one, how that I think of it). I can’t even hear the word “wisdom” without also thinking of strength, intelligence, dexterity, constitution and charisma – the rest of the Dungeons & Dragons player character abilities. If you aren’t familiar with Dungeons & Dragons, you may have found these episodes hard to understand or relate to, or perhaps even irritating. If that is the case, I’m sorry, but rest assured, there will be no D&D references in this episode beyond this point: I think we can consider that game as having been sufficiently mined for wisdom already. Hopefully one of these other games will resonate with you better.

Now, what is a game, exactly? Games are a ridiculously broad category. And many and various are the lessons, warnings and inspirations we can take from them. They can be the nerdiest things ever, like the game I just said I’m not going to mention, or brutally physical. Sports are games. The Hunger Games are games. Games can be social, or solitary – solitaire. They can be competitive, cooperative, or both. They can have vast audiences of spectators or none at all.

Some games are all skill, like chess. Others are all randomness, like roulette. Most are somewhere in between and maybe one of the things they teach us is how to operate in a world of semi-predictable probabilities. The whole branch of mathematics that deals with probability was developed to understand games of chance in the 17th century. Pascal and Fermat were basically commissioned to figure out how to count cards. That’s why we even understand probability.

Games range from the most innocent childhood pastime, like my daughter’s Sorry, to “den of sin” vices, casino gambling or the gladiatorial games of ancient Rome; from no stakes to the ultimate stakes. I just mentioned Pascal; his famous theological wager, on eternal stakes, is also a sort of game, a Gedankenspiel.

What all these games have in common is that they are all a form of practice life, they isolate some aspect of real life and exercise it outside of its normal context, for pleasure mostly, and maybe also for improvement – improvement of attitude and approach if not of skill. We like life, but maybe we feel a little thwarted and stuck in our particular life, games provide another way to come at it, for the elan vital to get exercised. Here, in this simplified way, is a way to feel progress, even if we aren’t feeling much, or any, in real life. And maybe in the process we learn or practice something to get us unstuck in real life.

It’s interesting to consider how games fit into the larger concept of play. Cats play; they pleasurably practice catching mice with their tails. But they don’t play games. Games have structure, rules. Maybe that’s the difference. But it’s a spectrum. When my cat and I chase each other around the house there are definitely some conventions we both respect. First he bites my foot, then I chase him, then we wrestle, then he makes this ridiculous snuffling noise, then he chases me. At the other end of the spectrum, we also call artistic performances play; they are even more rule-bound than games, because each performance or a piece of music or theater is in some sense, at least ideally, the same. There’s a script or a score, the notes are the same, the lines are the same. It’s like two players agreeing to always make the same moves in a game of chess. That wouldn’t be a game. A game is different every time, it’s unpredictable, that seems intrinsic to it. The cat plays with its tail, we play Monopoly, the actor plays Hamlet. So three kinds of pleasurable practice, escapist practice, the difference being the amount of structure and the amount of predictability.

But back to games-games.

I’m focusing mostly on board games today, but I just want to quickly mention video games and their great lesson of gamification. We’re always hearing about how we should gamify real life tasks and chores to motivate us to do them, which mostly involves introducing some structure for giving ourselves points, little self-induced dopamine rushes for hitting goals or following rules. I do that big time with Spider Hunter, my CBT for anxiety game, which is basically gamified exposure therapy. Gamification is running what games usually do in reverse: instead of practicing life, we’re making life seem more like practice.

There’s an element of gamification in any system that tracks progress – personal punch cards, the Lifelog, any system that I track using these. And I think it can be helpful to wake up to that aspect and be aware of it, to take better advantage of it. Gamification makes whatever task you’re tackling more interesting – more important. But also less scary, so in a sense, less important, less overwhelming. It lightens the mood. Even weight watchers, which I’m not a fan of in general, incorporates some degree of explicit gamification: in its more recent iterations it talks about “points” instead of calories.

There are all kinds of specialized apps you can use to gamify tasks and habits. But you don’t need them. A spreadsheet is the greatest gamification tool ever devised. Simple to get started with and infinitely configurable. It’s great for actual game design, too, apparently. Elizabeth Hargrave, designer of Wingspan, and self professed spreadsheet nerd, said that Wingspan started as a spreadsheet. For the truly old school an index card or a notebook might even be sufficient. For weekend luddites like me, a combination is ideal.

Personally, I’m not so into video games. Part of the reason, I think, at least originally, is that I was blessed with very little talent for them. But part of it is that I’ve learned the lesson of gamification so well that my whole life is a sort of video game. Who needs Sims when you’ve got the Lifelog? Every moment of every day I could be getting points for doing or not doing or noticing or suffering something.

Competition is one of the most fundamental aspects of games. And that makes sense. It’s a pretty fundamental aspect of life, and a difficult one to navigate. Because we aren’t purely, unreservedly competitive. Some level of competition is necessary, useful, for us and society as a whole. But too much, or not the right way, is destructive. We have to balance it with cooperativeness, with respect for our opponents, who are also often our families and dear friends and always, as the great psychologist Alfred Adler puts it, our Mitmenschen, our co-mensches, our fellow humans. In one form or another, games help us practice achieving this balance: competition and cooperation, capitalism and socialism, ancient Greek arete with early Christian “everything in common.”

Some games do competition in a very simple, one-sided way. They are on the surface simply competitive and the lesson, beyond how to win, is to learn how not to hate your opponents. The most perfect expression of this simple competition that I’ve played is Citadels, which encourages you, almost requires you to ruthlessly deceive and undermine your opponents. The idea is you are building a medieval city to a certain level of development while hobbling other players’ efforts to do it before you. Lots of scope for practicing forgiveness on simulated offenses. So much scope, in our family’s experience, that sometimes the lesson goes over students’ heads.

Then there’s the genre of cooperative games. There are a bunch of games for little kids like this. And mostly, honestly, they’re pretty boring. The lesson one perhaps unintentionally learns from these is that it can be boring to be too nice. Pandemic is the only grown-up game I know that actually pulls it off in a satisfying way, partially I think because unlike the kiddy cooperative games the stakes feel really high. There’s the subject matter for one thing (I still can’t believe that they thought of this game before covid), and the fact that it’s just really hard to win, the world usually winds up getting overrun by plagues, so the missing thrill of competition is adequately compensated for by the elevated sense of danger. And the working together is intense, sometimes even straight-up tense, when you don’t quite agree what to do. The translucent cubes for the four disease types are aesthetically satisfying too. They have this great dangerous science vibe -- radioactive biohazard. The four diseases don’t have names, just colors, so of course everyone comes up with their own. My family’s are scarlet fever, yellow fever, black death, and blue discomfort.

Those are the two ends of the cooperation/competition spectrum. But some games manage to keep elements of both: Wingspan is like this. Wingspan is a game about collecting birds. It immerses you in the natural world with these hundreds of beautiful, scientifically detailed bird cards.Wingspan has elegant, satisfying mechanics. Each game is slightly but significantly different, so it has infinite replay value. It’s totally absorbing without being stressful, even if you’re losing.

Most of our escapism is to horrible dystopias, imaginary places that are even more violent and stressful and monstrous than the real world, so it’s so refreshing and clean and a much better escape to go here among these beautiful and fascinating creatures. You will start being interested in birds if you aren’t already. Wingspan-inspired birdwatching turned out to be another great pandemic activity for us that has stuck.

Wingspan is a competitive game, but it’s not always zero sum. There are what my family calls “nicey powers,” cards that give your fellow-players a benefit along with whatever, usually greater, benefit they give you when you play them. Wyrmspan, an offshoot of Wingspan involving dragons, also has so called “friendly ties” for round end goals, with everyone getting full points instead of dividing them in case of a tie, which takes a little edge off the ruthlessness of the competition (and makes the math easier): for a round at least, everybody can win.

Goals are another fundamental part of games. This overlaps with competition but not 100%. You are incentivised to do something, you are trying to accomplish something, often that is or helps to win the game overall, but not always. In Wingspan goals are really interesting. There are several kinds of goals. Personal bonus card goals for the whole game. Round end goals that you compete with other players for. Game end scoring categories that function as subgoals. And of course, winning the game overall – which can sometimes feel like a detail. Because one of the beautiful things about Wingspan is that these various subgoals can be so satisfying that you feel good losing a game if you’ve hit one or more of these that you had your heart particularly set on. Sometimes you get so caught up in a subgoal that it’s detrimental to winning the game as a whole. And you consciously prefer it. It’s not a mistake, it’s an aesthetic choice. An instrumental goal can become, rightly, an intrinsic goal.

Our favorite round end goal in Wingspan is the very zen sounding “no goal.” In terms of Wingspan mechanics, “No Goal,” which sounds like a missed opportunity, is actually great in terms of developing your “engine” for longer term scoring, especially if it comes early on in the game. So we’re always delighted when we get it. And it’s helped me appreciate the value of letting go of goals every now and then in real life. Not always – goals are often, maybe even mostly necessary and good. But sometimes. The good life is a balance of goal and no goal. You’ve probably heard such a thing before. It’s not exactly a new insight. But there’s a difference between hearing wisdom and rehearsing it over and over again, enacting it over and over again, and feeling, in some little way, that it works.

I’ve mentioned how Wingspan starts you off with a different combination of birds and goal cards each game and how that makes each game unique, right from the start. Other games also do this. Smallworld does it in a particularly ingenious and satisfying way. In Smallworld, you control a race of fantasy creatures (demihumans) whose qualities are determined by sticking together the bare race itself, with some randomly selected descriptive qualifier. Your race then tries to conquer and hold onto as much territory in the game as possible, competing against other players for a share of this very limited space. Sometimes the race-attribute combinations are very powerful, sometimes they are ridiculous and surprising, which is where I extract most of my wisdom from this mechanism. You get combinations like “Commando Halflings” or “Diplomatic Rat Men” There are a bunch of ways I use this insight to organize my own habits, but one that jumps to mind is how I distribute my weekly tasks (especially my housecleaning tasks) by day of the week with a mnemonic label attached to the name of the day and starting with the same letter: “Medsitative make-up Mondays,” “Tub and toilet Tuesdays,” “Self-reflective stovesauger Saturdays,” etc. Our real life “small worlds,” our homes, are probably bigger than we’d like when it comes to keeping them tidy and clean, where we are really limited is time. Having these cutesy task labels, these day of the week name slogans, helps me get a handle on these hard-to-squeeze-in tasks. I can’t forget them and it takes my stress level down a notch because they’re playful and I now have this pleasant association of the game Smallworld with them.

I’ve already mentioned randomness and skill. My family’s favorite games are a good blend of both. Pure skill games means the better player always or usually wins. That can be stressful and boring and not ideal for familial harmony. I appreciate the intellectual beauty of chess, but I’m not sure how much I enjoy actually playing it; I’m always glad when it’s over and there isn’t smoke coming out of anyone’s ears. Pure chance can be equally stressful and boring. The combination is more satisfying, and more like life: skillfully making the best of the hand you’re randomly dealt. It’s like the serenity prayer: accept your hand with a good grace, change the bits you do have control over. Again, it’s obvious, it’s not new, the serenity prayer has been around for a while, but the practice, the enactment of it, adds something.

Well, that seems like a good place to stop for today. There are more games I love, with yet more wisdom, but I think you get the point. More than any particular nugget of wisdom, here’s a stream to pan for it in. That’s the point I want to make. I wish you luck – and fun – panning for your own. Thanks for listening.

© 2002-2025 Everyday Systems LLC, All Rights Reserved.